On April 22, 1970, 8 years after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published, 1 year after a fire on the Cuyahoga River (then a common occurrence) gained national attention, and several months before the official creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, the United States observed the first Earth Day. After the idea for a nationwide grassroots Earth Day was proposed by Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, universities organized teach-ins, activists in cities gathered people for rallies, and others organized educational events, increasing national awareness of environmental issues and care about protecting the environment. Today, Earth Day is celebrated globally and, according to the Earth Day Network, is “the largest secular civic event in the world.” Many individuals in our local community were present at an Earth Day event in 1970, and we have invited two of them to share their reflections on how they were involved with Earth Day then, how the spirit of Earth Day has influenced their life and/or their work, the changes they have seen in the environment and environmentalism in the past 50 years, and how they plan to celebrate Earth Day 2020. Do you have a story from the first Earth Day? Please share in the comments!

Curt Rowell

Curt Rowell is a resident of Phillipsburg, NJ. After a long career in photography and printing he assumed management of the Easton Urban Farm for two seasons and is currently constructing a film-based analog photo lab.

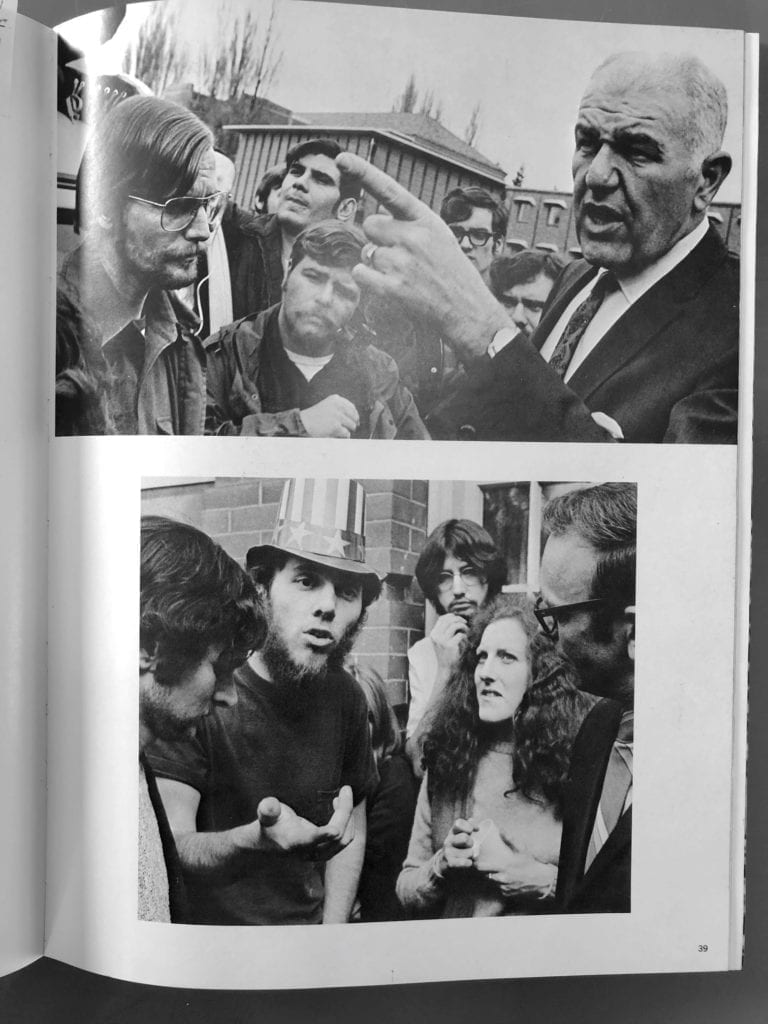

1970 Yearbook pics. Top: campus confrontations – Vietnam Vets with college administrator, Bottom: Curt as Uncle Sam

“April 22, 1970 was just a blip on my radar. I was 19, draft age, and a sophomore in college in Bellingham, Washington. The world in my eyes and the eyes of my peers was in turmoil, largely because of the incursion by the US government into countries of Southeast Asia. It is not within the scope of this reminiscence to chronicle the events or the outcomes other than to point to the institutional racism, the number of ‘peacetime’ deaths and the drug addiction originating with the cheap and plentiful heroin available to soldiers in that war. Without a student deferment, draft age males were conscripted to fight it. The ranks of the Army were disproportionately filled by young African American men and others who could not gain admission or could not afford college. That was my focus, the anti-war movement.”

While his attention was on the anti-war movement, Curt had direct experience with the environmental issues of the time and remembers the work of other activists and members of “countercultural” circles who were active on those issues.

“I can provide some local background to that first Earth Day, however, in the not so pristine northwest corner of Washington State. The forests had been subject to clear cutting for decades. There was a Georgia Pacific ‘industrial tissue’ (aka toilet paper) mill on the waterfront of the city center. It emitted an odor as did other towns on Puget Sound, which for Bellingham suggested canned tuna and sulphur. North of town was an aluminum smelting facility that emitted fluorine and the withering effect on vegetation could be seen from the highway. And a few miles to the northwest was an oil refinery preparing to host supertankers coming down from Alaska, snaking their way through foggy, island-choked inland waterways.

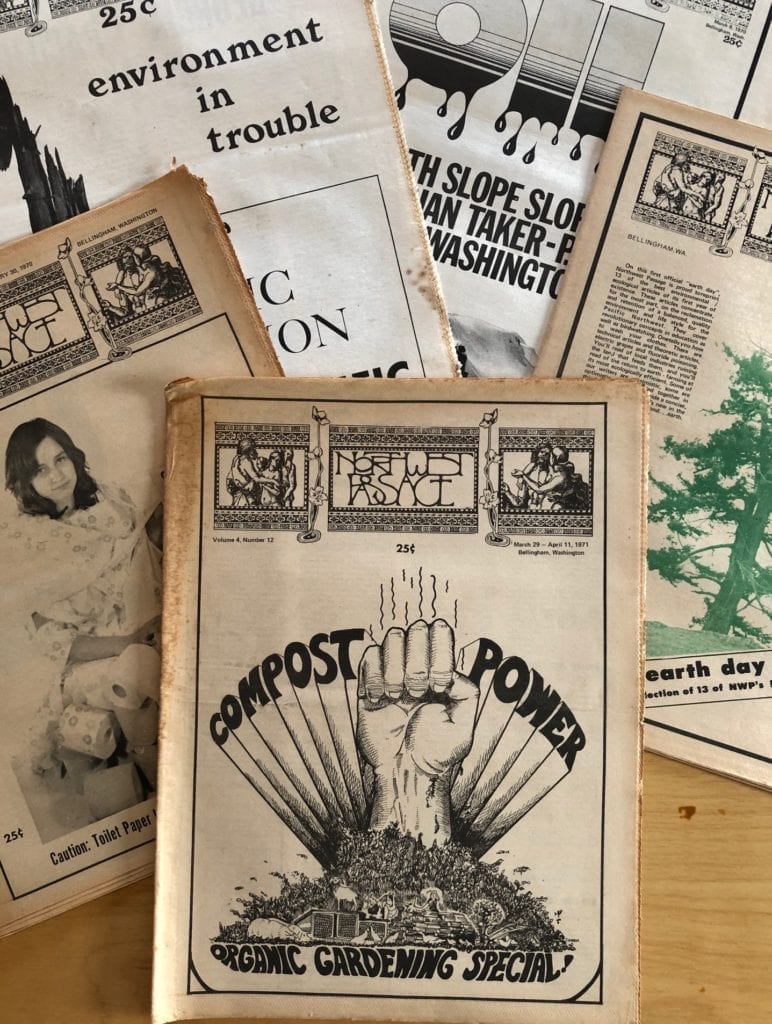

My antiwar fervor led me to the ‘Underground’ biweekly community tabloid, The Northwest Passage, which addressed countercultural lifestyle and the environment. In a dive through those yellowed newspapers this afternoon, I came across one mention of an environmental fair to be held in Seattle, 90 minutes south of Bellingham, in April of 1970. There was also a special Earth Day edition of the Passage which reprinted some of the better researched articles on those aforementioned industries.”

As years passed and the issues of the world shifted, Curt notes that “the spirit of Earth Day began to resurface” in his life. “I’ve started to recognize that the primary threat to our wellbeing as a species is the wellbeing of the planet,” he says. Curt describes how in the 90s he began to grow more connected to environmentalism, particularly sustainable agriculture projects.

“Barry Commoner headlined an environmental mobilization that I attended in New York City and I recall my toddler daughter in the baby backpack. I received a gift subscription to the Organic Gardening magazine, which publicized the winter symposium of the NJ chapter of the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) in 1998. I traveled from Manhattan by NJ Transit to Rutgers in New Brunswick and met organic farmers and some of those chosen to help forge the National Organic Standards (NOS). Organic Agriculture in the US showed the promise of food supply chain disruption and a challenge to corporate chemical and petroleum driven growing practices. Now living in Easton, I became a CSA member in 1999, assuming an extreme workshare position at the Asbury Village Community Farm (Warren County, NJ) for the next 15 years. We delivered food to the Occupiers in Zuccotti Park in 2011.

I also attended Rutgers Environmental Stewards training in 2014 to become a citizen scientist. A sense of powerlessness had lingered for many years after the antiwar movement; that feeling began to subside.”

Curt’s interest in sustainable agriculture also led him to work with the Easton Urban Farm, which is central to his plans for Earth Day this year.

“For 5 years we had informal gatherings at the Urban Farm, mostly around food, on Earth Day. For 2020, 50 years [since the first Earth Day], when I think about 5 decades and progress on a movement to ensure the longevity of our civilization, which is sort of the essence of our environmental struggles – climate change and global warming in particular – and when you think about what has been accomplished in 5 decades earlier in American history, I’m wondering if it should be a day of mourning, and if I should be putting on the black armband that may encourage me and others to reflect on our failure. However, I will invoke the line from this movie called Home – and this is about the only narration in the whole film – ‘it’s too late to be a pessimist.’ So that being said, better not to dwell on our failures, but on our little accomplishments at whatever scale we’ve chosen to try to take action. These could be simple tasks to reduce our footprint on this earth, such as embracing a plant-based diet.

I probably will take a stroll over to the Urban Farm. It’s a refuge. It’s a wildlife habitat. It represents, to me, hope. My affirmation and talk track for Earth Day 2020 is a phrase invoked in Stewards training: No one can do everything, but everyone can do something; attributed to Helen Keller.

There are three environmental voices I would like to credit for their vision and leadership, and none are Caucasian males: Maya K. van Rossum who is our Delaware Riverkeeper; Michele Byers, longtime Executive Director of the New Jersey Conservation Foundation; and Steve Curwood who has been broadcasting weekly from Cambridge at Living on Earth for 30 years.”

All photos provided by Curt Rowell.

Dr. Diane Husic

Dr. Diane Husic is Dean of the School of Natural and Health Sciences and a Professor of Biology at Moravian College. Her research focuses on the restoration of a contaminated site (the Palmerton Superfund site) and the impact of climate change on the Appalachian landscape. She also works with science communication, citizen science, and international policies addressing climate change as a credentialed observer for the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change.

“In April 1970 I was in sixth grade, and I really don’t remember anything from the first Earth Day itself, but the next year when I entered middle school, I’m pretty sure my teachers had been influenced by it. They were great naturalists and great storytellers, and they took us out on field trips for hikes and to forage for wild edibles and to make maple syrup in the spring. The other thing I really remember is collecting newspapers for recycling for the first time. People didn’t do that before, and the “tree-hugger” movement got started at that time.

We talked a lot about saving trees, and we also had a lot of class discussions about a range of environmental issues. The filmstrips they showed had images of disfigured landscapes from coal mines and acid runoff into the rivers and they were always from Pennsylvania! I grew up in Michigan and they showed all of these horrible things from the steel industry; I had no idea I would eventually move here someday. We don’t always realize how early influences will impact us later, but those post-Earth Day #1 lessons from 7th and 8th grade about contamination in PA were almost a foreshadowing of the restoration work that I do at the Palmerton Superfund Site and the Lehigh Gap.

In addition to educational experiences, Diane’s background spending a lot of time in nature and exploring the areas around her shaped her interest in the environment.

“I spent my formative years, including college, along the shoreline of Lake Superior and in the forests of mixed hardwoods, white birch, and pines. It is a place where childhood free time is filled with berry picking, cross-country skiing, or diving into the icy waters of ‘the big lake.’

Reflecting on the role the outdoors played in her early life, Diane says, “Growing up, my best friend Sue and I imagined ourselves as amateur explorers and spent as much time as possible in nature. When we get together (we have been friends for over 50 years), we still explore wild places.” Pictured here are a bog in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Diane with her friend Sue, and Lake Superior as viewed from Presque Isle Park in Marquette, MI.

I am sure that these experiences had an influence on the way I interact with and view the planet. Today, my students come to a class probably more aware of the concepts like ozone layer damage or climate change or acid rain than when I first started teaching in the ‘80s, but we rarely see students who (and I’m overgeneralizing here) are naturalists. They can’t identify or describe things in nature, or if I tell them they can go out and actually find things that are edible in the spring they look at me like ‘you gotta be crazy,’ or ‘that could kill you.’”

Passionate about people connecting to the earth and to nature, Diane provides advice for caring for the environment as a society and carrying the spirit of Earth Day forward.

“We can retell the story of Earth Day in the 1970s. It’s a time to make connections between the environment and our health again, which was really at the root of the 1970s. People were worried about contaminants and the quality of air and water and their health. I think there’s some really good readings or even short videos from Katharine Hayhoe asking the question, ‘is COVID-19 linked to climate change?’ And the answer is, not really. But [Hayhoe] goes on to talk about other environmental disruptions and I played that for my students and they loved it (See Diane’s blog post reflecting further on COVID-19, climate change, and our relationship to the environment). Second, get people outside to notice the beauty and the simple things. I had my students do a reflection paper after their Costa Rica trip – and they wrote ‘it was very peaceful’ or ‘we didn’t have to worry about certain things.’ In the after reflection, they realized how it affected them, so getting people outdoors, even if it disrupts their comfort level a little bit, will have an impact. Lastly, one of the things we all need is hope. I love taking students to the Lehigh Gap Nature Center. If you can take a contaminated moonscape and restore it to a wildlife refuge that is open to the public, it can’t help but give hope for all of us to realize that rejuvenation is possible. Conservation, land preservation, citizen restoration and science are all things that we can do to make a positive environmental difference.”

As a professor, Diane regularly interacts with college students who weren’t alive until almost 30 years after the first Earth Day. She reflects on how the younger generation is approaching environmental issues and the example that the movement surrounding the first Earth Day could set for people coming together and taking a stand.

“The regulations that were put into place [after Earth Day 1970] – the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, the banning of DDT – ultimately made, at least in the US, the environment a lot better. For those of us who were around then, we see the difference. We see the cleaner rivers, the cleaner air, but now we also have these big global issues like climate change, questions about food security, and so on. When I talk to students, they haven’t seen that incremental change, both for the better in terms of how much of a role the environmental regulations have played and [for the worse] how dramatic the changes from things like climate change have been. They don’t realize that that movement [environmentalism around the first Earth Day in the ‘60s and ‘70s] played a role in creating important legislation, and when I try to talk to them about the impacts of the deregulation we’re in now, they’re saying ‘well, there’s nothing we can do about it.’

Diane with colleagues and students at the 25th Conference of Parties (COP25) for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

So there’s this sense of defeatism. What I really think we need is a movement – having attended the UN climate meetings with students since 2009 (see photo from COP25 in Dec 2019), I have witnessed first-hand the common global concern about climate change and the hope that we can come together to address this challenge. Greta [Thunberg] represents the new form of activism and I think she is doing much to inspire youth, and all of us. Such individual actions like hers have led to a global movement — not unlike what led to the first Earth Day and the subsequent regulatory actions. Not everyone is willing to be an activist, but those that are can call attention to important issues, educate the broader citizenry leading them to advocate for change, etc. We need these movements more than ever!”

Lastly, Diane describes how she will observe Earth Day on April 22 this year and how she honors and works to protect the earth throughout the year.

“By coincidence, Moravian College is holding its annual InFocus symposium and it’s on Earth Day this year. The theme is actually poverty and inequality, but I’ve been asked to organize a panel around the UN meetings ‘From Paris Agreement to COP25: An Analysis of the UN Process.’ My comments will focus on the role of scientists as knowledge brokers, working at the science policy interface or with the public, trying to bring the science to climate action. Students often ask what I do to decrease my carbon footprint or walk-the-conservation-walk. Well, last year, a group of colleagues and I formed a company and purchased (saved) 500 acres of rainforest in Costa Rica! (Read more in another of Diane’s blog posts!)” The borders are currently closed there, but I can’t wait to get back.

All photos provided by Dr. Diane Husic.

NNC is grateful to Curt Rowell and Dr. Diane Husic for sharing their stories reflecting on 50 years of Earth Day, and for their ongoing work to connect people to our planet and protect its environment.

While the specific priority issues or types of celebrations involved in Earth Day 2020 likely look different than they did in 1970, the general spirit of the holiday remains the same. By recognizing our relationship to our natural world, we see how improving the earth’s wellbeing also improves human wellbeing. We give thanks for the planet we live on and join with others in doing our part to protect it. Even though we can’t gather in person to celebrate Earth Day this year, we can each hopefully spend some time outside, as Diane suggests, take a moment to appreciate our relationship to the planet, and remember Curt’s affirmation: “no one can do everything, but everyone can do something.” Happy Earth Day!