Do you think your neighbors are more or less concerned about environmental issues than they were 10 years ago? How does this compare to opinions across the United States? Would the majority of people support or oppose new government measures to protect open space? These are just a few examples of the many questions that Dr. Chris Borick of Muhlenberg College and his research team have sought to answer through public opinion polling at the national, state, and regional levels. Good quality data of this kind allows programs and policies to draw on a better understanding of what the public’s interests are, making them more responsive to people’s desires and ultimately more effective in achieving their goals.

Do you think your neighbors are more or less concerned about environmental issues than they were 10 years ago? How does this compare to opinions across the United States? Would the majority of people support or oppose new government measures to protect open space? These are just a few examples of the many questions that Dr. Chris Borick of Muhlenberg College and his research team have sought to answer through public opinion polling at the national, state, and regional levels. Good quality data of this kind allows programs and policies to draw on a better understanding of what the public’s interests are, making them more responsive to people’s desires and ultimately more effective in achieving their goals.

If you’ve heard Chris Borick’s name before, it might well have been during election season, when everyone wants to check the polls to see who is projected to win a particular race. However, Dr. Borick comments that although he understands the interest in watching the polls, to him, “that’s the very least important role that public opinion research should play. What I like the most is around policy – what do people care about? What do they want, what do they want to see done? What are they worried about?”

As Director of the Institute of Public Opinion at Muhlenberg, Dr. Borick pursues this type of public opinion research beyond election polling. “Our overarching goal is to measure public attitudes, views, beliefs, needs, and knowledge on a number of areas in the Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania, and nationally,” he says. This includes gathering data for a variety of projects related to environmental issues.

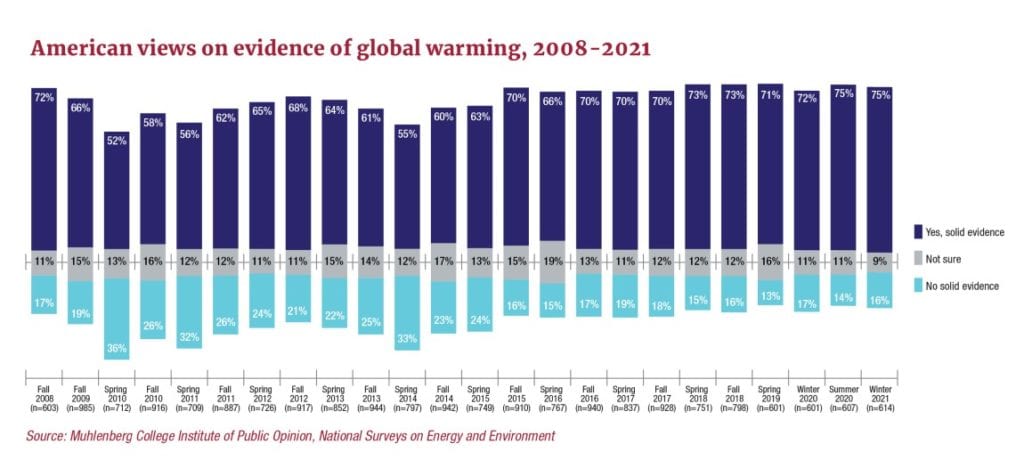

Acceptance of climate change declined around when Dr. Borick first started administering this survey, but has since rebounded and become more stable.

One such project, the National Survey on Energy and Environment, has been asking Americans about their views on climate change twice a year since 2008. This has resulted in a database of over 23,000 individuals’ responses to questions about whether they accept climate change, how concerned they are about it, how confident they are in what climate scientists are saying, which policies they support, and more. “I’ve been given a lot of insight as to how Americans look at this issue,” Dr. Borick says. Over the years, his research team has been able to observe how a variety of factors influence the public’s acceptance of climate change. “Around 2008 to 2010 or 2011, we actually saw a decline,” Dr. Borick explains. “[acceptance] went from 70% down all the way to 50% [of the population] in a pretty short period of time. It was really driven by leaders, ‘elites,’ sending out messages and cues that were skeptical of climate change. It was also during an economic downfall, and there were some other weather related factors. That’s really rebounded in the last decade. Around 2012 it started to go up, and then what’s really interesting is about 4-5 years ago it started to steadily be in the 70-75% acceptance level among Americans and it hasn’t budged. That’s one of the big parts of the story — it’s more durable, more stable now.”

Amidst these changes in national opinion, what has been happening in the Lehigh Valley? In all likelihood, trends have followed similar lines locally. “The general story is that how it plays [out] here is pretty indicative of the national trends.” Dr. Borick says. “I think that says a lot about the Valley itself – how we’re made up. You’ve got urban areas, rural areas, mixed partisan – definitely pretty strong Democrat and Republican cohorts in the area. You’ve got emerging demographic groups – people of color, Latinx communities – growing like they are nationally. Suburban areas – wealthy, growing economically advantaged areas. You put it all together, and no place is a perfect microcosm for the country, but it does pretty good at being a bellwether.” This is evident during national election cycles as well, when the Lehigh Valley receives a lot of attention because results here often mirror results nationally.

The Lehigh Valley is fortunate to have a lot of green areas, even in close proximity to its cities. This open space is a top priority among residents in Valley-wide surveys.

Dr. Borick also regularly conducts Lehigh Valley-specific surveys as well as state-wide surveys on environmentally-related topics, each reaching 400-500 participants. Every spring as part of their public health program, his research team does a Pennsylvania public health survey asking, among other things, about radon, climate change, fracking, and perceived public health risks related to the environment. Regional quality of health studies ask about environmental conditions, focusing on air and water quality, land use, preservation, and open space. “It’s those open space issues that are often really important to people in the area,” Dr. Borick says, “and that’s probably not shocking with a lot of the land use changes, expansion of warehouses, disappearance of open space in areas of the Valley. It really resonates with people, sometimes even more than underlying air and water quality issues.” Dr. Borick explains that when the importance of open space first emerged in these surveys, it was surprising to him that it was a top priority for people. This is an example of how looking at public opinion data can change one’s pre-existing assumptions about what the general public thinks. “One of the things as a public opinion researcher, of course I have my underlying beliefs of what I think people know or feel or want,” he says, “but often I’m wrong! It’s neat to see that – that’s why you do the work and the surveys, because what you think might not be right.”

That experience of finding an unexpected result underscores the importance of conducting public opinion research. “Without that type of research, we’re guessing at what the public wants,” remarks Dr. Borick. Since it’s hard to predict what people are thinking without asking them in some systematic way, those guesses would often be wrong. Just because it seems like “everyone” is most worried about a particular topic or in support of a particular policy doesn’t mean that’s actually the case, and public opinion polls are one way of getting more reliable information about public preferences. “The public can express its wants through voting, protests, and outreach to elected officials, but one of the other big ways that we can do that is to try to scientifically and empirically measure what the public wants,” Dr. Borick says. If officials want to start a program that promotes renewable energy or expands a city’s park system or adds new bike lanes, it’s important for them to be able to demonstrate that they have public support. In Dr. Borick’s words, “in a democracy where the will of the people should guide their elected officials and have it impact what elected officials do, measuring those wants, concerns, views, and needs of the people becomes important.”